Thread Starter

#1

These are the photographs of Mercedes Benz 300SL which is the oldest existing SL-Class on earth. It has been recently restored by Mercedes Benz in order to commemorate the 60th anniversary of SL-Class. According to Mercedes Benz:

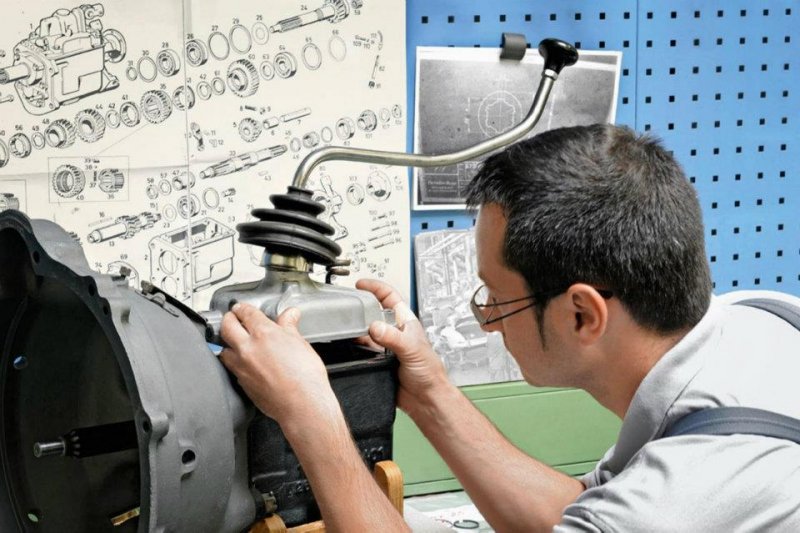

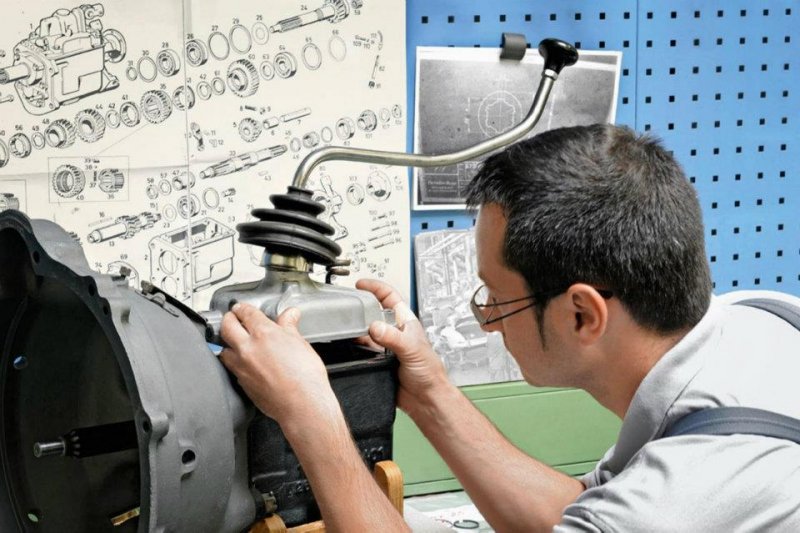

A cardinal rule of building racecars is “simplify, then add lightness.” There was plenty done to the end of lightness in chassis #2 such as a magnesium transmission bell housing. As for simplifying things, what you see on the blueprint in the background is about as simple as a 4-speed syncro-mesh manual transmission gets.

That large platter-shaped object is the hand-fabricated air filter housing and if you’re wondering why it’s so far off to one side, it’s because the only way that the straight-six engine would fit under the hood was to tilt it 50 degrees to the left. And when we say “fit” we mean just: there’s all of 1 centimeter between the air filter housing and the hood.

The fully restored interior of chassis #2—just because it was designed as a racecar didn’t mean the driver had to be uncomfortable. And take a look at the speedo and tach: you’ll see their design reflected in the gauges in the all-new SLK and SL.

Aluminum-intensive construction, separated by 60 years.

Stripped bare of paint, the chassis #2’s hand-crafted aluminum body awaits restoration at the Classic Center in Fellbach, Germany.

All you need are seats and a steering wheel, and you could drive it away. The body on chassis #2 (and every subsequent Gullwing) was basically just aerodynamic cladding. Also, you get a better look at the engine. Using tried and true hot rodding methods, Rudy Uhlenhaut and his team took the three-liter straight-six out of the dignified “Adenauer” sedan (the equivalent of today’s S-Class) and got to work, fabricating their own cylinder head with hotter cams and better-breathing Solex racing carburetors. Finally, they tilted it 50 degrees to the left so it would fit, then gave it dry-sump lubrication so it could sit lower in the chassis. The net result was a jump in horsepower from 115 to 170; by the end of the original 300SL’s production run, power was up to 222 hp—good for an honest 160 mph in a day when 110 was a stretch for most high-performance sports cars.

Primed and ready for its first new coat of paint in 60 years, you can easily see the imperfect fit between chassis #2’s body panels. That’s because every one of them was literally hand-made—it’s just not possible to get the tolerances that mechanical stamping is capable of that way. Still, there’s something to be said about building an entire car body with nothing but hammers, English wheels and bare hands.

Notice how smooth chassis #2’s flanks are—not a door seam to be seen. Of course, that begs the question, where are the doors? They’re right where they should be, except that on the early 300SLs, they didn’t go any lower than the driver’s side window. Sure, they made getting in and out difficult, but they also made for smoother overall airflow, which meant just that much more speed. They may have stayed that way, too, had it not been for racing’s governing body mandating larger doors.

Not even the once-ubiquitous Mercedes-Benz tartan plaid seat upholstery can survive 60 years unscathed. Note the holes in the seat frame—since chassis #2 was built as a racecar, weight was saved wherever it could be, and that meant using as little metal as possible but stopping short of compromising structural integrity.

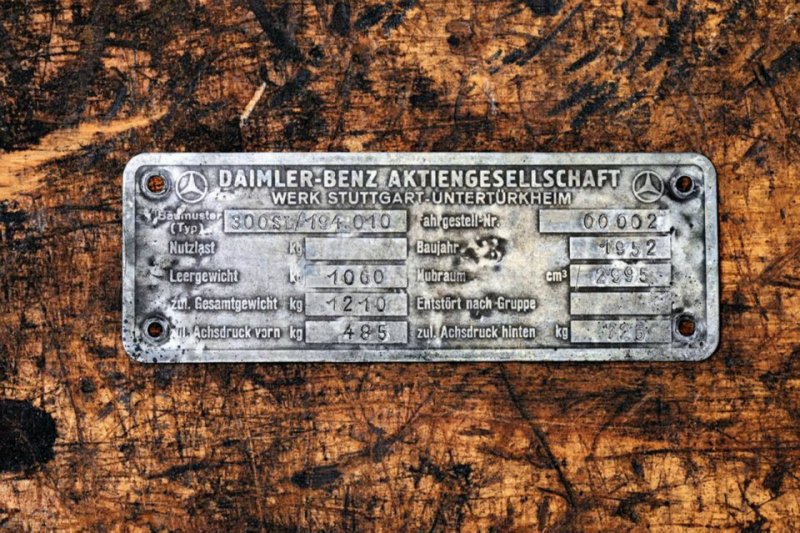

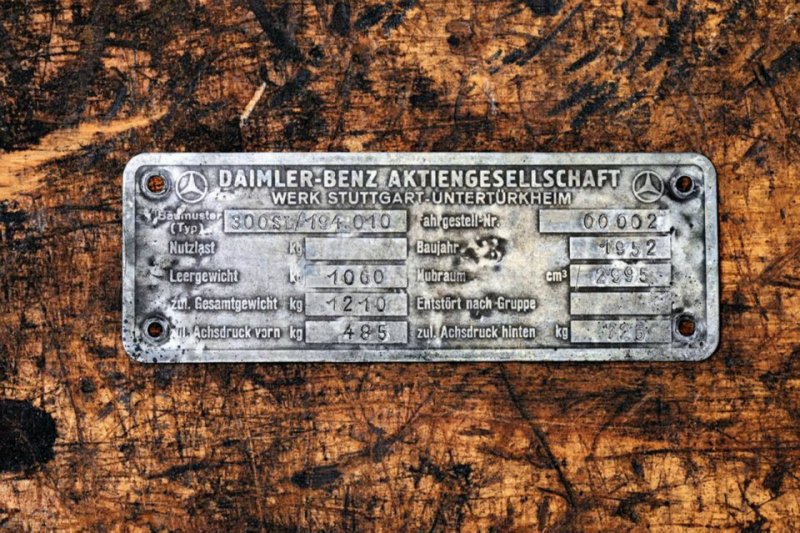

Everything you need to identify chassis #2 for what it is.

See that leather strap? In the days before hood pins, that’s how you kept the hood from flying open at high speeds.

One of chassis #2’s front suspension towers. Notice the holes—when we said weight was saved everywhere, we meant it. A note about the front axle: as you might expect it was drilled out to save weight, but curiously, it was also nickel-plated. Nobody at the Classic Center could figure out why until an old hand pointed out that the nickel plating made potentially dangerous hairline cracks visible to the pit crew.

If you wanted to open a window, that small cow flap was it. In fact, the windows weren’t actually glass, but rather aircraft-grade Plexiglas. Again, all in the name of saving weight.

Made of high-strength alloy tubes in a pattern of interlocking triangles, the 300SL’s spaceframe chassis was not only incredibly light, but incredibly stiff, as well. Part of that was thanks to the tall side sills, but of course that meant regular doors couldn’t be fitted to the SL. Yes, that’s right: the gullwing doors were not a stylistic flourish, but rather the only way to get in and out of the car.

Part of what made the 300SL a great endurance racer was how much could fit under that trunk. For one thing, an absolutely gigantic fuel tank gave it long distance range. For another, there was still enough room in there to fit two full-size spare wheels and tires.

Assuming there’s a total of six men holding chassis #2’s body, we can figure that each one is holding a little more than 18 lbs each—the entire body only weighed 110 lbs.

Chassis #2 getting its second coat of paint 60 years after its first, but other than the color, the two have nothing to do with one another. The original paint was a semi-gloss nitro-cellulose lacquer, but of course nitro-cellulose-based paints have long been banned for environmental reasons. However, through exhaustive research of period color photographs, the original paint supplier was able to produce a water-based version of “silver bronze,” the official racing color at the time.

Fully restored and back in action, chassis #2 stretches its legs a bit. You can still find a hot rod-style side-exit exhaust on the G55 AMG.

(Pictures and Caption: Mercedes Benz USA)

Drive Safe,

350Z

“The restoration of the bodywork was particularly tricky. It's made out of extremely fine aluminium/magnesium sheet metal, which, by its very nature, is extremely delicate. Time had also taken its toll on it in many places. It took the specialists around six months to bring the body shell... back to its former glory. The restoration... lasted ten months in all, which, in view of the extensive work involved, represented a very tight schedule.”

That large platter-shaped object is the hand-fabricated air filter housing and if you’re wondering why it’s so far off to one side, it’s because the only way that the straight-six engine would fit under the hood was to tilt it 50 degrees to the left. And when we say “fit” we mean just: there’s all of 1 centimeter between the air filter housing and the hood.

The fully restored interior of chassis #2—just because it was designed as a racecar didn’t mean the driver had to be uncomfortable. And take a look at the speedo and tach: you’ll see their design reflected in the gauges in the all-new SLK and SL.

Aluminum-intensive construction, separated by 60 years.

Stripped bare of paint, the chassis #2’s hand-crafted aluminum body awaits restoration at the Classic Center in Fellbach, Germany.

All you need are seats and a steering wheel, and you could drive it away. The body on chassis #2 (and every subsequent Gullwing) was basically just aerodynamic cladding. Also, you get a better look at the engine. Using tried and true hot rodding methods, Rudy Uhlenhaut and his team took the three-liter straight-six out of the dignified “Adenauer” sedan (the equivalent of today’s S-Class) and got to work, fabricating their own cylinder head with hotter cams and better-breathing Solex racing carburetors. Finally, they tilted it 50 degrees to the left so it would fit, then gave it dry-sump lubrication so it could sit lower in the chassis. The net result was a jump in horsepower from 115 to 170; by the end of the original 300SL’s production run, power was up to 222 hp—good for an honest 160 mph in a day when 110 was a stretch for most high-performance sports cars.

Primed and ready for its first new coat of paint in 60 years, you can easily see the imperfect fit between chassis #2’s body panels. That’s because every one of them was literally hand-made—it’s just not possible to get the tolerances that mechanical stamping is capable of that way. Still, there’s something to be said about building an entire car body with nothing but hammers, English wheels and bare hands.

Notice how smooth chassis #2’s flanks are—not a door seam to be seen. Of course, that begs the question, where are the doors? They’re right where they should be, except that on the early 300SLs, they didn’t go any lower than the driver’s side window. Sure, they made getting in and out difficult, but they also made for smoother overall airflow, which meant just that much more speed. They may have stayed that way, too, had it not been for racing’s governing body mandating larger doors.

Not even the once-ubiquitous Mercedes-Benz tartan plaid seat upholstery can survive 60 years unscathed. Note the holes in the seat frame—since chassis #2 was built as a racecar, weight was saved wherever it could be, and that meant using as little metal as possible but stopping short of compromising structural integrity.

Everything you need to identify chassis #2 for what it is.

See that leather strap? In the days before hood pins, that’s how you kept the hood from flying open at high speeds.

One of chassis #2’s front suspension towers. Notice the holes—when we said weight was saved everywhere, we meant it. A note about the front axle: as you might expect it was drilled out to save weight, but curiously, it was also nickel-plated. Nobody at the Classic Center could figure out why until an old hand pointed out that the nickel plating made potentially dangerous hairline cracks visible to the pit crew.

If you wanted to open a window, that small cow flap was it. In fact, the windows weren’t actually glass, but rather aircraft-grade Plexiglas. Again, all in the name of saving weight.

Made of high-strength alloy tubes in a pattern of interlocking triangles, the 300SL’s spaceframe chassis was not only incredibly light, but incredibly stiff, as well. Part of that was thanks to the tall side sills, but of course that meant regular doors couldn’t be fitted to the SL. Yes, that’s right: the gullwing doors were not a stylistic flourish, but rather the only way to get in and out of the car.

Part of what made the 300SL a great endurance racer was how much could fit under that trunk. For one thing, an absolutely gigantic fuel tank gave it long distance range. For another, there was still enough room in there to fit two full-size spare wheels and tires.

Assuming there’s a total of six men holding chassis #2’s body, we can figure that each one is holding a little more than 18 lbs each—the entire body only weighed 110 lbs.

Chassis #2 getting its second coat of paint 60 years after its first, but other than the color, the two have nothing to do with one another. The original paint was a semi-gloss nitro-cellulose lacquer, but of course nitro-cellulose-based paints have long been banned for environmental reasons. However, through exhaustive research of period color photographs, the original paint supplier was able to produce a water-based version of “silver bronze,” the official racing color at the time.

Fully restored and back in action, chassis #2 stretches its legs a bit. You can still find a hot rod-style side-exit exhaust on the G55 AMG.

(Pictures and Caption: Mercedes Benz USA)

Drive Safe,

350Z

![Clap [clap] [clap]](https://www.theautomotiveindia.com/forums/images/smilies/Clap.gif) to see an old, dying car being brought back to life again to turn a wheel in anger. Kudos to all the people who were involved in this restoration project for their brilliant effort.

to see an old, dying car being brought back to life again to turn a wheel in anger. Kudos to all the people who were involved in this restoration project for their brilliant effort.